“Le poète mourant”: Whisper of a Shadow

Louis Moreau Gottschalk: La Nouvelle-Orléans via Haiti, Cuba, Brazil, and beyond

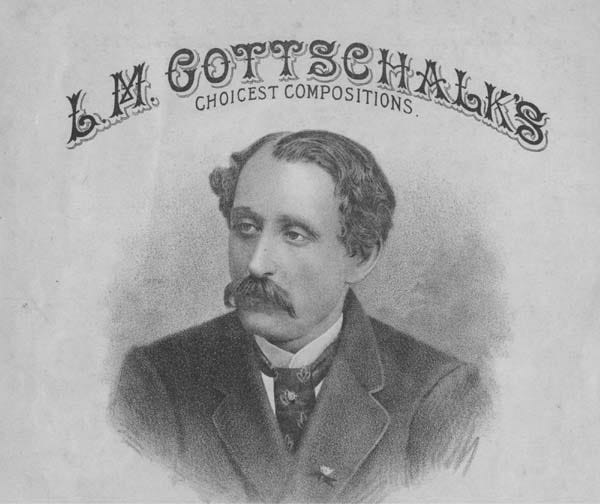

New Orleans has been oriented to the French and Spanish Caribbean since the slave-trade era. Composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829-1869), born in this Latin American cultural crossroads of German Jewish and Haitian Creole heritage, grew up with a Haitian nanny, and traveled and performed extensively in Europe, Haiti, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Colombia, Ecuador, and Brazil, all places where he found musical inspiration.

The first internationally recognized, distinctively U.S. classical composer, Gottschalk incorporated his itinerant musical explorations in his compositions. Likewise, he engaged with and inspired such noted composers as Cubans Ignacio Cervantes and Manuel Saumell, Brazilian Ernesto Nazareth, and Texas-born Scott Joplin, among others.

Gottschalk’s life and music comprise the inspiration for French trumpeter-composer-ethnomusicologist Yohan Giaume’s Whisper of a Shadow, the creative product of the artist’s own musical sojourn through Cuba, Argentina, Uruguay, Peru, North Africa, Europe, and New Orleans.

The recording opens with Giaume’s arrangements of two Gottschalk compositions, “Le poète mourant” (invoking the last piece Gottschalk performed before collapsing on stage from yellow fever in Rio de Janeiro, where he died soon thereafter at the age of 40) and “Mascarade” (with a pointed monologue by Chuck Perkins that deflates polite fictions about the congenial minstrel-show invisible man entertaining the nominally white New Orleans elite).

On “Cold Facts,” Perkins narrates the 1873 Easter Sunday massacre in Colfax, Louisiana, where ex-Confederate soldiers, KKK brigands, and the Knights of the White Camelia mobbed and murdered some 150 black folk, a brutal response to Reconstruction:

The Red River flowed past a scarlet fire beneath a magenta sky.

In Colfax, Louisiana, this courthouse sits on sacred ground

Baptized by the crimson blood of freedom seekers

Consecrated by the bones of 150 children of god

My disbelieving eyes located the placard, it said

Their death represented the end of Carpetbagger misrule

And the Ancestors fill pity for small men

Who can’t give up their colossal fantasies of supremacy

The horns blare and the birds sing morning glory

The tears of the shadows marks the affront

The grass don’t grow and fire don’t burn no more

But dreams still breathe, the ancestors will be honoredOn Easter Sunday 1873, three died fighting for white supremacy

A hundred-and-fifty died fighting to live

But counter to that, the closing triptych (“Life Circle Part 1 Death—Passage—Life Circle Part 2 Birth”) concludes with a joyous, brassy, percussive Second-Line affirmation.

Giaume’s key collaborator is New Orleans clarinetist Evan Christopher, who oriented Giaume to the Big Easy and brought several local luminaries to the project, among them Nicholas Payton (trumpet), Greg Hicks and Terrance Taplin (trombone), Matt Perine (tuba), Aaron Diehl (piano), Roland Guerin (bass), Herlin Riley (drums), and Chuck Perkins (spoken word). Together they convey the living musical spirit of New Orleans in this deep, wide-ranging, and historically engaged opus, the first of a series of recordings Giaume envisions.

With the musical culture of New Orleans, Giaume observes, “everything is connected, every musical line or rhythm you play is the shadow of something that came from somewhere, and it is fascinating to me to see how cultural heritage continues to exist after centuries of geographical transformations.” Consider this, his exploration of the work of a visionary 19th-century New Orleans composer’s early essay on what U.S. American classical music might become.