Jazz: America’s classical music?

As what we imagine “jazz” to be morphs in international territory, rooted certainties meet divergent improvisatory sensibilities, drawing the classic jazz canon into more expansive crosscurrents.

Recordings Reviewed

Arturo O'Farrill and the Afro Latin Jazz Orchestra

Fandango at the Wall: A Soundtrack for the United States, Mexico and Beyond

Resilience MusicJowee Omicil

Love Matters

Jazz VillageSons of Kemet

Your Queen Is a Reptile

Impulse!

The categorical declaration that “jazz is America’s classical music” expresses a certain curatorial certitude and sense of exclusiveness that underplays the authenticity of improvised music produced or rooted anywhere else on the planet. How to play free of the canonic straitjacket that fetishizes pedigree, technique, the obligatory nod to New Orleans, and formulaic invocations of an at least partly imagined musical past?

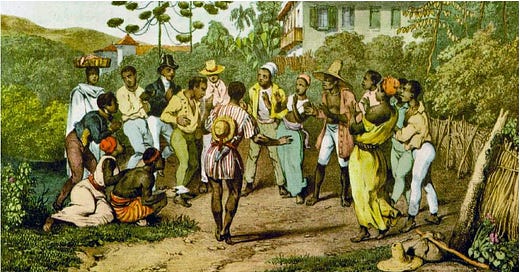

Consider some iconoclastic exceptions: Sun Ra, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, and Frank Zappa, to name but a few. Likewise, offshore, various projects—Mulatu Astatke, The Heliocentrics, Tony Allen, what we designate Latin jazz (the diverse strains of Cuba, Puerto Rico, Haiti, Panama, Brazil and beyond), the jazz scenes of Toronto, London, France, Spain, Germany, Poland, Hungary, South Africa, Japan—all exemplify just how variously creative approaches to improvisation can be in actual practice. The recordings auditioned here suggest that, as jazz evolves in a global milieu, the canon’s rooted certainties give way to approaches that take the North American formulary in evocative and illuminating new directions.

On the US-Mexico border, the CD-book-documentary project titled Fandango at the Wall is the creation of Cuban American pianist-composer-bandleader Arturo O’Farrill, conceived in reaction to the tide of xenophobia unleashed during the 2016 presidential campaign. For this project O’Farrill recruited writer, bassist, composer and Grammy-winning producer Kabir Sehgal, as well as Jorge Francisco Castillo, a retired librarian and producer of the annual Fandango Fronterizo Festival, a cross-border cultural encounter that highlights the son jarocho song and dance tradition of southeastern Mexico.

The project convenes an eclectic mix of artists and combines live May 2018 performances on the San Diego-Tijuana border with supporting studio work. Performers include Mandy González (the singer of Hamilton fame); jazz violinist Regina Carter; drummer Antonio Sánchez; the Villalobos Brothers (violins, vocals); Chilean rapper Ana Tijoux; Iraqi American oudist-singer-composer Rahim AlHaj; and Persian tar master Sahba Motallebi. They join an array of son jarocho artists in communion with Arturo O’Farrill and the Afro Latin Jazz Orchestra.

The first of this two-CD set concentrates primarily on the guest artists, mixing Afro Cuban, Middle Eastern and Latin American folk idioms. It ends with three son jarochos that anticipate the focus of the second disc, and the founding impetus of the fandango confab itself. Disc two essays the son jarocho, with both traditional material and new compositions by some of the genre’s most accomplished interpreters, Patricio Hidalgo Belli (jarana, vocals), Ramon Gutiérrez Hernández (requinto, vocals), Fernando Guadarrama Olivera (jarana, vocals), Tacho Utrera (leona, vocals) and numerous others.

In a country where, in debased popular parlance, the term “immigrant” connotes an ominous threat of terrorist invasion, Fandango at the Wall argues persuasively for the edifying capacity of cross-cultural encounters to break through both material and metaphorical walls that are rooted in a moral panic of ignorance, fear, racism, nationalism, and the structuring forces of the neoliberal market economy.

A consonant tale of displacement runs through the artistry of Jowee Omicil, born to Haitian emigrants in Montreal. A minister’s son, Omicil started playing the saxophone for his father’s congregation before studying at Berklee College of Music (he also plays clarinet, cornet, flute, and Fender Rhodes, manifesting influences from Ornette Coleman to Monk, Miles, Roy Hargrove, the folk strains of Haiti, Martinique and Spanish-speaking Latin America, as well as rap, Afrobeat and Mozart). Omicil performed in Haiti and Panama before making Paris his home. Love Matters! draws from the same Avignon session as his idiosyncratic 2017 debut, Let’s BasH!

On Omicil’s “Rara Demare,” which invokes Haiti’s carnival tradition, there is an element of Sidney Bechet circa 1938–1940 (Bechet plumbed his own Caribbean roots in Haitian meringue and what was at the time was denominated as rhumba). Calypso comes through on “Marie-Clémence,” while Omicil’s cover of the Venezuelan folk tune “Duérmete mi niño,” with a reggae-like beat, thereby reflecting an omnivorous regional outlook.

Then there is “Be Kuti,” a manifest reference to Fela Kuti, the reigning legend of Afropop (Omicil has performed with Kuti collaborator Tony Allen). And we leave it to readers to imagine the captivating spiral of Omicil’s “Mozart BasH!”

The most pointedly political of these artists is London-based Sons of Kemet, whose Your Queen Is a Reptile is an unabashed repudiation of Elizabeth, Victoria and the royal revenant. Per the liner notes, “We the immigrants, we the children of immigrants, we the diaspora, we the descendants of the colonized, we claim our right to question your obsolete systems, your racist symbols, your monuments to genocide…. We claim a place at the table, and we say your history is not pure, your empire is not whole, your conscience is not clean, your money was printed in blood, your high horse is three-legged, and your royalty wears no clothes. Your queen is not our queen. She does not see us as human. And we know what we came here to do.”

Leader and tenor saxophonist Shabaka Hutchings is named after the Egyptian Pharaoh and founder of the 25th dynasty. Born in London but expatriated to Barbados at age six, Hutchings came up as a school band clarinetist concurrently immersed in Barbadian calypso, carnival music, soca, and recordings from Jamaica and the U.S. He returned to London to study classical clarinet at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama.

Hutchings works with tuba tunesmith Theon Cross and two drummers, Tom Skinner and Eddie Hick, and guest vocalists in a combo different from a typical jazz quartet. Still, sonically this rhythm-n-brass formulation owes something to New Orleans, as it does to the military brass bands that grew out of the European colonial adventure wherever it landed.

Yet, as part of the Caribbean diaspora and successors of the Windrush Generation, Hutchings et al. draw as well upon the energy of reggae artists like Anthony B, Capleton (Clifton George Bailey III), and Sizzla, as well as Kendrick Lamar, Tupac, Notorious B.I.G. and others. Your Queen Is a Reptile celebrates the lives and contributions of a different sort of royalty, black women both well and lesser known.

The opening track, “My Queen Is Ada Eastman,” is a tribute to Hutchings’ Barbadian grandmother, the family matriarch and “the person who inspires me to get up in the morning and try to get better at whatever I’m doing.” Among other tributes are those to Harriet Tubman, a frenetic double-time march; Angela Davis, where sax and tuba trade licks and slide into octave unison; and in a nod to Jamaican resistance to slavery, the laid-back nyabinghi allusions of “My Queen Is Nanny of the Maroons.”

Beyond their ease with jazz as classically defined, what unites these artists is their independence from received norms, and a readiness to experiment and draw from myriad sources, reflecting the cosmopolitan character and globe-ranging experience of the artists themselves. These titles convey a pervasive sense of cultural and political intentionality, an inclusive conception of world musics, a contrarian sense of world history, and a conviction that beyond technical mastery, music may serve to bring people together in inspiring and powerfully enlightening ways.

As Hutchings observes, “Not being from the place that jazz was born means I don’t feel any ultimate reverence to it. It is just about finding ways of reinterpreting how we are thinking about the music, re-envisioning it, just completely decontextualizing it and saying it is up for grabs.” Or, as Jowee Omicil might put it, “Let’s Bash” (with apologies to Ornette Coleman) in the shape of music to come.