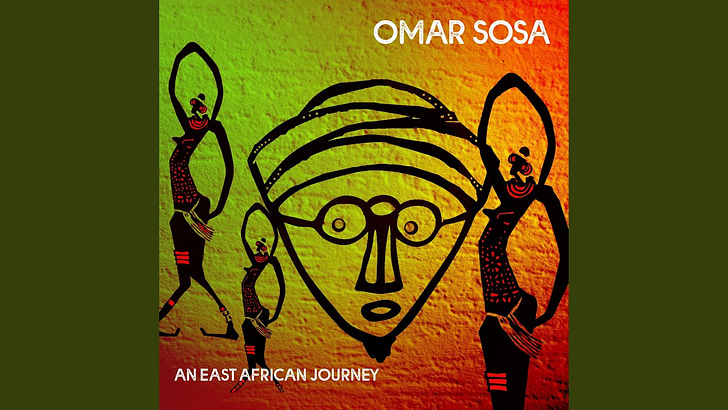

An East African Journey

Cuban pianist-composer Omar Sosa engages with artists in Madagascar, Zambia, Ethiopia, Sudan, Burundi, Kenya, and Mauritius

In 2009, pianist Omar Sosa’s French booking agent 3D Family set up a tour of eight Alliance Française sites in East Africa, as filmed by French documentary filmmaker Olivier Taïeb. Joining Sosa were two longtime collaborators, singer Mola Sylla (Senegal) and bassist Childo Tomas (Mozambique). Taïeb’s documentary Souvenirs d’Afrique debuted on France’s MEZZO TV the following year, while Sosa’s evocative field recordings of traditional artists inspired him, back in the studio, as he developed his own complementary piano improvisations.

As Sosa predicted in 2010, a busy touring and recording schedule would delay this title’s realization for a decade. Omar and Steve Argüelles, his Paris-based co-producer, took up the project again while finalizing Transparent Water (Otá), Sosa’s singular collaboration with Senegalese singer, percussionist, and kora master Seckou Keita. In Paris, along with Sosa’s piano, Argüelles added tasteful and restrained drums and percussion, augmented by the work of bassist and synth player Christophe Minck.

A creative synthesis of close and sympathetic listening across half a continent, An East African Journey (Otá) achieves what few so-called “world music” undertakings ever manage. Sosa’s playing is restrained throughout, engaging with, complementing, and building upon the subtle creations of his artistic partners, rather than using their striking and diverse talents as mere spice for his own work. What makes this title more compelling still is its departure from European and North American artists’ more typical turn to West Africa for genre-bounding musical inspiration.

Consider “Che Che,” krar (5–string Ethiopian lyre) player and singer Seleshe Damessae’s nonpareil vocal evocation of a galloping horse. Just as unlikely is Omar’s engagement with Monja Mahafay of Madagascar, who sings and plays marovany (24–string box zither) and lokanga (3–string violin), the latter on “Sabo,” whose rhythmic exhalations invoke the spirits who carry the deceased to the realm of the ancestors. And Sosa conjures a serious groove on Kenyan singer Olith Ratego’s “Thuon Mok Loga.”

Every piece is its own revelation, revealing their essence more fully with each new listening. The spirit of relaxed, knowing collaboration comes across joyfully on “Shibinda,” with Abel Ntalasha, the Zambian singer and player of the kalumbu, a single-stringed instrument reminiscent of the Brazilian berimbau. We hear the banter between the artists (with Joseph Chibiya on backing vocals) on an endless percussive loop that would be equally at home in an all-night Cuban rumba session. Closing the album is Mauritius frame drum (ravanne) player Menwar on the meditative “Ravann Dan Jazz,” pointing toward Omar’s next unpredictable horizon.

Different still from the preceding is the sonic chemistry between Omar and Madagascar’s Rajery (vocals and valiha, an 18–string bamboo-tube zither) on “Tsiaro Tsara,” “Veloma E,” and “Dadilahy,” each unique yet perhaps together the tracks most readily accessible to those searching beyond the aural bounds of Western musical convention. But even to say that risks diminishing the animating collaborative genius of An East African Journey, one more expression of Omar Sosa’s stated determination never to play the same thing twice.